Margaret Atwood’s Nashville Debut

It was her first time in Nashville. She used to listen to the Grand Ole Opry in the cold winter of northern Canada. When they got short wave radio reception. So because it was her first time in Nashville she sang. So she could say that she did.

She reached way back into the Hank Williams vault and pulled out this:

Why don’t you love me like you used to do

How come you treat me like a worn out shoe

My hair’s still curly and my eyes are still blue

Why don’t you love me like you used to do

Made me love her more. Even more than I used to. And I’ve been appreciating Margaret Atwood for over 20 years. A friend sitting next to me wondered aloud before the evening got started if she would be good at speaking to college students. Not all authors or other famous folks can connect to every audience. And sometimes they talk over or under the heads of those right in front of them.

Not Margaret Atwood. She was right on the mark. Her assignment, the theme of the conference, was to talk about imagined communities. And she has imagined some doozies in the last three or four decades. In her opening remarks she described utopias and dystopias. The good ideal communities (utopias) in literature often contain within them little seriously flawed communities (dystopias) she said. And vise versa.

I first read her now-classic novel in the early 1990s. Handmaid’s Tale is set in a dystopian society. It’s a world in which civil liberties have been renounced out of fear. Regimes of terror, anxiety and control reign supreme. What I remember is the devastating physical and psychological pain inflicted on the nameless narrator who spins out her story of torture and humiliation. She tells about Baptist guerrillas, freedom fighters, hiding in the hills. I remember feeling shame and pride alternately as I read that book.

I also greatly admire Cat’s Eye, which is about an artist giving a retrospective of her paintings. The story that Atwood weaves is also a retrospective of the artist’s life. In her late childhood and early adolescence, the leading character, Elaine, is snared in traps that young girls set for each other. She suffered under the oppressive control of her so-called “friends.” That book felt like it held many autobiographical moments. But who can say for sure?

Another friend of mine had the great privilege of introducing Atwood. He said she, like other great authors and interpreters, gives us the gift of helping us see what we might ordinarily miss: the very contexts in which we live. Indeed her books have done this for me. I’m ready to get her latest books, Oryx and Crake (2004) and The Year of the Flood (2010), a whole book, which take place “meanwhile . . .” Or as Atwood called it: “a simultequel” (“I made that up,” she quipped.)

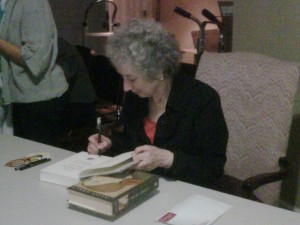

She took questions at the end. She’s heard them all she says. The students lined up at the microphones to ask her things like: Can you tell us about your writing process? And why does the main character in Handmaid’s Tale have no name? And what shaped the feminist impulses in your writing? And why does the main character suck his fingers so much? She was mostly direct, always charming, occasionally evasive and endlessly interesting in her responses.

By all the marks I could see, Margaret Atwood’s Nashville debut was a success.